Anti-Chinese sentiment

Anti-Chinese sentiment (also referred to as Sinophobia) is the fear or dislike of Chinese people and/or Chinese culture.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

It is frequently directed at Chinese minorities which live outside Greater China and involves immigration, nationalism, political ideologies, disparity of wealth, the past tributary system of Imperial China, majority-minority relations, imperial legacies, and racism.[7][8][9][note 1]

A variety of popular cultural clichés and negative stereotypes of Chinese people have existed around the world since the twentieth century, and they are frequently conflated with a variety of popular cultural clichés and negative stereotypes of other Asian ethnic groups, known as the Yellow Peril.[12] Some individuals may harbor prejudice or hatred against Chinese people due to history, racism, modern politics, cultural differences, propaganda, or ingrained stereotypes.[12][13]

The COVID-19 pandemic led to resurgent Sinophobia, whose manifestations range from as subtle acts of discrimination such as microaggression and stigmatization, exclusion and shunning, to more overt forms, such as outright verbal abuse, slurs and name-calling, and sometimes physical violence.[14][15][16][17][18]

History

[edit]Looting and sacking of national treasures

[edit]Historical records document the existence of anti-Chinese sentiment throughout China's imperial wars.[19]

Lord Palmerston was responsible for sparking the First Opium War (1839–1842) with Qing China. He considered Chinese culture "uncivilized", and his negative views on China played a significant role in his decision to issue a declaration of war.[20] This disdain became increasingly common throughout the Second Opium War (1856–1860), when repeated attacks against foreign traders in China inflamed anti-Chinese sentiment abroad.[citation needed] Following the defeat of China in the Second Opium War, Lord Elgin, upon his arrival in Peking in 1860, ordered the sacking and burning of China's imperial Summer Palace in vengeance.[citation needed]

Chinese Exclusion Act 1882

[edit]In the United States, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed in response to growing Sinophobia. It prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers and turned those already in the country into second-class persons.[21] The 1882 Act was the first U.S. immigration law to target a specific ethnicity or nationality.[22]: 25 Meanwhile, during the mid-19th century in Peru, Chinese were used as slave labor and they were not allowed to hold any important positions in Peruvian society.[23]

Chinese workers in England

[edit]Chinese workers had been a fixture on London's docks since the mid-eighteenth century, when they arrived as sailors who were employed by the East India Company, importing tea and spices from the Far East. Conditions on those long voyages were so dreadful that many sailors decided to abscond and take their chances on the streets rather than face the return journey. Those who stayed generally settled around the bustling docks, running laundries and small lodging houses for other sailors or selling exotic Asian produce. By the 1880s, a small but recognizable Chinese community had developed in the Limehouse area, increasing Sinophobic sentiments among other Londoners, who feared the Chinese workers might take over their traditional jobs due to their willingness to work for much lower wages and longer hours than other workers in the same industries. The entire Chinese population of London was only in the low hundreds—in a city whose entire population was roughly estimated to be seven million—but nativist feelings ran high, as was evidenced by the Aliens Act of 1905, a bundle of legislation which sought to restrict the entry of poor and low-skilled foreign workers.[24] Chinese Londoners also became involved with illegal criminal organisations, further spurring Sinophobic sentiments.[24][25]

By region

[edit]East Asia

[edit]Korea

[edit]Discriminatory views of Chinese people have been reported,[26][27] and ethnic-Chinese Koreans have faced prejudices including what is said, to be a widespread criminal stigma.[28][29] Increased anti-Chinese sentiments had reportedly led to online comments calling the Nanjing Massacre the "Nanjing Grand Festival" or others such as "Good Chinese are only dead Chinese" and "I want to kill Korean Chinese".[30][28]

Japan

[edit]A survey in 2017 suggested that 51% of Chinese respondents had experienced tenancy discrimination.[31] Another report in the same year noted a significant bias against Chinese visitors from the media and some of the Japanese locals.[32]

Mongolia

[edit]Mongolian nationalist and Neo-Nazi groups are reported to be hostile to China,[33] and Mongolians traditionally hold unfavorable views of the country.[34] The common stereotype is that China is trying to undermine Mongolian sovereignty in order to eventually make it part of China (the Republic of China has claimed Mongolia as part of its territory, see Outer Mongolia). Fear and hatred of erliiz (Mongolian: эрлийз, [ˈɛrɮiːt͡sə], literally, double seeds), a derogatory term for people of mixed Han Chinese and Mongol ethnicity,[35] is a common phenomena in Mongolian politics. Erliiz are seen as a Chinese plot of "genetic pollution" to chip away at Mongolian sovereignty, and allegations of Chinese ancestry are used as a political weapon in election campaigns. Several small Neo-Nazi groups opposing Chinese influence and mixed Chinese couples are present within Mongolia, such as Tsagaan Khas.[33]

Southeast Asia

[edit]Malaysia

[edit]Due to race-based politics and Bumiputera policy, there had been several incidents of racial conflict between the Malays and Chinese before the 1969 riots. For example, in Penang, hostility between the races turned into violence during the centenary celebration of George Town in 1957 which resulted in several days of fighting and a number of deaths,[36] and there were further disturbances in 1959 and 1964, as well as a riot in 1967 which originated as a protest against currency devaluation but turned into racial killings.[37][38] In Singapore, the antagonism between the races led to the 1964 Race Riots which contributed to the expulsion of Singapore from Malaysia on August 9, 1965. The 13 May Incident was perhaps the deadliest race riot to have occurred in Malaysia with an official combined death toll of 196[39] (143 Chinese, 25 Malays, 13 Indians, and 15 others of undetermined ethnicity),[40] but with higher estimates by other observers reaching around 600-800+ total deaths.[41][42][43]

Malaysia's ethnic quota system has been regarded as discriminatory towards the ethnic Chinese (and Indian) community, in favor of ethnic Malay Muslims,[44] which has reportedly created a brain drain in the country. In 2015, supporters of Najib Razak's party reportedly marched in the thousands through Chinatown to support him, and assert Malay political power with threats to burn down shops, which drew criticism from China's ambassador to Malaysia.[45]

It was reported in 2019 that relations between ethnic Chinese Malaysians and Malays were "at their lowest ebb", and fake news posted online of mainland Chinese indiscriminately receiving citizenship in the country had been stoking racial tensions. The primarily Chinese-based Democratic Action Party in Malaysia has also reportedly faced an onslaught of fake news depicting it as unpatriotic, anti-Malay, and anti-Muslim.[46]

Philippines

[edit]The Spanish introduced the first anti-Chinese laws in the Philippine archipelago. The Spanish massacred or expelled the Chinese several times from Manila, and the Chinese responded by fleeing either to La Pampanga or to territories outside colonial control, particularly the Sulu Sultanate, which they in turn supported in their wars against the Spanish authorities.[47] The Chinese refugees not only ensured that the Sūg people were supplied with the requisite arms but also joined their new compatriots in combat operations against the Spaniards during the centuries of Spanish–Moro conflict.[48]

Furthermore, racial classification from the Spanish and American administrations has labeled ethnic Chinese as alien. This association between 'Chinese' and 'foreigner' have facilitated discrimination against the ethnic Chinese population in the Philippines; many ethnic Chinese were denied citizenship or viewed as antithetical to a Filipino nation-state.[49] In addition to this, Chinese people have been associated with wealth in the background of great economic disparity among the local population. This perception has only contributed to ethnic tensions in the Philippines, with the ethnic Chinese population being portrayed as being a major party in controlling the economy.[49]

Indonesia

[edit]

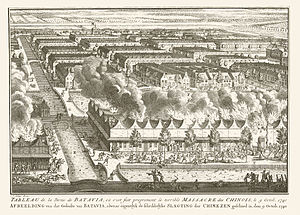

The Dutch introduced anti-Chinese laws in the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch colonialists started the first massacre of Chinese in the 1740 Batavia massacre in which tens of thousands died. The Java War (1741–43) followed shortly thereafter.[50][51][52][53][54]

The asymmetrical economic position between ethnic Chinese Indonesians and indigenous Indonesians has incited anti-Chinese sentiment among the poorer majorities. During the Indonesian killings of 1965–66, in which more than 500,000 people died (mostly non-Chinese Indonesians),[55] ethnic Chinese were killed and their properties looted and burned as a result of anti-Chinese racism on the excuse that Dipa "Amat" Aidit had brought the PKI closer to China.[56][7] In the May 1998 riots of Indonesia following the fall of President Suharto, many ethnic Chinese were targeted by other Indonesian rioters, resulting in extensive looting. However, when Chinese-owned supermarkets were targeted for looting most of the dead were not ethnic Chinese, but the looters themselves, who were burnt to death by the hundreds when a fire broke out.[57][58]

Myanmar

[edit]Chinese people in Myanmar have also been subject to discriminatory laws and rhetoric in Burmese media and popular culture.[59]

Thailand

[edit]Historically, Thailand (called Siam before 1939) has been seen as a China-friendly country, owing to close Chinese-Siamese relations, a large proportion of the Thai population being of Chinese descent and Chinese having been assimilated into mainstream society over the years.

In 1914, King Rama VI Vajiravudh originated the phrase "Jews of the Orient" to describe Chinese.[60]: 127 He published an essay using Western antisemitic tropes to characterize Chinese as "vampires who steadily suck dry an unfortunate victim's lifeblood" because of their perceived lack of loyalty to Siam and the fact that they sent money back to China.[60]: 127

Later, Plaek Phibunsongkhram launched a massive Thaification, the main purpose of which was Central Thai supremacy, including the oppression of Thailand's Chinese population and restricting Thai Chinese culture by banning the teaching of the Chinese language and forcing Thai Chinese to adopt Thai names.[61] Plaek's obsession with creating a pan-Thai nationalist agenda caused resentment among general officers (most of Thai general officers at the time were of Teochew background) until he was removed from office in 1944.[62]

Vietnam

[edit]There are strong anti-Chinese sentiments among the Vietnamese population, stemming in part from a past thousand years of Chinese rule in Northern Vietnam. A long history of Sino-Vietnamese conflicts followed, with repeated wars over the centuries. Though current relations are peaceful, numerous wars were fought between the two nations in the past, from the time of the Early Lê dynasty (10th century)[63] to the Sino-Vietnamese War from 1979 to 1989.

Shortly after the 1975 Vietnamese defeat of the United States in the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese government persecuted the Chinese community by confiscating property and businesses owned by overseas Chinese in Vietnam and expelling the ethnic Chinese minority into southern Chinese provinces.[64] In February 1976, Vietnam implemented registration programs in the south.[65]: 94 Ethnic Chinese in Vietnam were required to adopt Vietnamese citizenship or leave the country.[65]: 94 In early 1977, Vietnam implemented what it described as a purification policy in its border areas to keep Chinese border residents to the Chinese side of the border.[65]: 94–95 Following another discriminatory policy introduced in March 1978, a large number of Chinese fled from Vietnam to southern China.[65]: 95 China and Vietnam attempted to negotiate issues related to Vietnam's treatment of ethnic Chinese, but these negotiations failed to resolve the issues.[65]: 95 During the August 1978 Youyi Pass Incident, the Vietnamese army and police expelled 2,500 refugees across the order into China.[65]: 95 Vietnamese authorities beat and stabbed refugees during the incident, including 9 Chinese civilian border workers.[65]: 95 From 1978 to 1979, some 450,000 ethnic Chinese left Vietnam by boat (mainly former South Vietnam citizens fleeing the Vietcong) as refugees or were expelled across the land border with China.[66]

The 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War resulted in part from Vietnam's mistreatment of ethnic Chinese.[65]: 93 The conflict fueled racist discrimination against and consequent emigration by the country's ethnic Chinese population.These mass emigrations and deportations only stopped in 1989 following the Đổi mới reforms in Vietnam.[citation needed]

South Asia

[edit]India

[edit]During the Sino-Indian War, the Chinese faced hostile sentiment all over India. Chinese businesses were investigated for links to the Chinese government and many Chinese were interned in prisons in North India.[citation needed] The Indian government passed the Defence of India Act in December 1962,[67] permitting the "apprehension and detention in custody of any person hostile to the country." The broad language of the act allowed for the arrest of any person simply for having a Chinese surname or a Chinese spouse.[68] The Indian government incarcerated thousands of Chinese-Indians in an internment camp in Deoli, Rajasthan, where they were held for years without trial. The last internees were not released until 1967. Thousands more Chinese-Indians were forcibly deported or coerced to leave India. Nearly all internees had their properties sold off or looted.[67] Even after their release, the Chinese Indians faced many restrictions on their freedom. They could not travel freely until the mid-1990s.[67]

Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]

The Chinese population was active in political and social life in Australia. Community leaders protested against discriminatory legislation and attitudes, and despite the passing of the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901, Chinese communities around Australia participated in parades and celebrations of Australia's Federation and the visit of the Duke and Duchess of York.

Although the Chinese communities in Australia were generally peaceful and industrious, resentment flared up against them because of their different customs and traditions. In the mid-19th century, terms such as "dirty, disease-ridden, [and] insect-like" were used in Australia and New Zealand to describe the Chinese.[69]

A poll tax was passed in Victoria in 1855 to restrict Chinese immigration. New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia followed suit. Such legislation did not distinguish between naturalised, British citizens, Australian-born, and Chinese-born individuals. The tax in Victoria and New South Wales was repealed in the 1860s.

In the 1870s and 1880s, the Growing trade union movement began a series of protests against foreign labour. Their arguments were that Asians and Chinese took jobs away from white men, worked for "substandard" wages, lowered working conditions, and refused unionisation.[70] Objections to these arguments came largely from wealthy land owners in rural areas.[70] It was argued that without Asiatics to work in the tropical areas of the Northern Territory and Queensland, the area would have to be abandoned.[71] Despite these objections to restricting immigration, between 1875 and 1888 all Australian colonies enacted legislation that excluded all further Chinese immigration.[71]

In 1888, following protests and strike actions, an inter-colonial conference agreed to reinstate and increase the severity of restrictions on Chinese immigration. This provided the basis for the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act and the seed for the White Australia Policy, which although relaxed over time, was not fully abandoned until the early 1970s.

The Chifley government's Darwin Lands Acquisition Act 1945 compulsorily acquired 53 acres (21 ha) of land owned by Chinese-Australians in Darwin, the capital of the Northern Territory, leading to the end of the local Chinatown. Two years earlier, the territory's administrator Aubrey Abbott had written to Joseph Carrodus, secretary of the Department of the Interior, proposing a combination of compulsory acquisition and conversion of the land to leasehold in order to effect "the elimination of undesirable elements which Darwin has suffered from far too much in the past" and stated that he hoped to "entirely prevent the Chinese quarter forming again". He further observed that "if land is acquired from the former Chinese residents there is really no need for them to return as they have no other assets". The territory's civilian population had mostly been evacuated during the war and the former Chinatown residents returned to find their homes and businesses reduced to rubble.[72]

New Zealand

[edit]In the 1800s, Chinese citizens were encouraged to immigrate to New Zealand because they were needed to fulfill agricultural jobs during a time of white labor shortage. The arrival of foreign laborers was met with hostility and the formation of anti-Chinese immigrant groups, such as the Anti-Chinese League, the Anti-Asiatic League, the Anti-Chinese Association, and the White New Zealand League. Official discrimination began with the Chinese Immigrants Act of 1881, limiting Chinese emigration to New Zealand and excluding Chinese citizens from major jobs. Anti-Chinese sentiment had declined by the mid-20th century.

Papua New Guinea

[edit]In May 2009, during the Papua New Guinea riots, Chinese-owned businesses were looted by gangs in the capital city Port Moresby, amid simmering anti-Chinese sentiment reported in the country.[73] There are fears that these riots will force many Chinese business owners and entrepreneurs to leave the South Pacific country, which would invariably lead to further damage on an impoverished economy that had a 80% unemployment rate.[73] Thousands of people were reportedly involved in the riots.[74]

Tonga

[edit]In 2000, Tongan noble Tu'ivakano of Nukunuku banned Chinese stores from his Nukunuku District in Tonga. This followed complaints from other shopkeepers regarding competition from local Chinese.[75]

In 2006, rioters damaged shops owned by Chinese-Tongans in Nukuʻalofa.[76][77]

Solomon Islands

[edit]In 2006, Honiara's Chinatown suffered damage when it was looted and burned by rioters following a contested election. Ethnic Chinese businessmen were falsely blamed for bribing members of the Solomon Islands' Parliament. The government of Taiwan was the one that supported the then-current government of the Solomon Islands. The Chinese businessmen were mainly small traders from mainland China and had no interest in local politics.[76]

Europe

[edit]

Anti-Chinese sentiment became more common as China was becoming a major source of immigrants for the west (including the American West).[9] Numerous Chinese immigrants to North America were attracted by wages offered by large railway companies in the late 19th century as the companies built the transcontinental railroads.

Anti-Chinese policies persisted in the 20th century in the English-speaking world, including the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, anti-Chinese zoning laws and restrictive covenants, the policies of Richard Seddon, and the White Australia policy

France

[edit]In France, there has been a long history of systemic racism towards the Chinese population, with many people stereotyping them as easy targets for crime.[78] As a result, France's ethnic Chinese population have been common victims of racism and crime, which include assaults, robbery, and murder; it is common for Chinese business owners to have their businesses robbed and destroyed.[78] There have been rising incidents of anti-Chinese racism in France; many Chinese, including French celebrity Frederic Chau, want more support from the French government.[79] In September 2016, at least 15,000 Chinese participated in an anti-Asian racism protest in Paris.[78]

Germany

[edit]In 2016, Günther Oettinger, the former European Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society, called Chinese people derogatory names, including "sly dogs", in a speech to executives in Hamburg and had refused to apologize for several days.[citation needed]

Italy

[edit]Although historical relations between two were friendly and even Marco Polo paid a visit to China, during the Boxer Rebellion, Italy was part of Eight-Nation Alliance against the rebellion, thus this had stemmed anti-Chinese sentiment in Italy.[80] Italian troops looted, burnt, and stole a lot of Chinese goods to Italy, many are still being displayed in Italian museums.[81]

Portugal

[edit]In the 16th century, increasing sea trades between Europe to China had led Portuguese merchants to China, however Portuguese military ambitions for power and its fear of China's interventions and brutality had led to the growth of sinophobia in Portugal. Galiote Pereira, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary who was imprisoned by Chinese authorities, claimed China's juridical treatment known as bastinado was so horrible as it hit on human flesh, becoming the source of fundamental anti-Chinese sentiment later; as well as brutality, the cruelty of China and Chinese tyranny.[82] With the Ming dynasty's brutal reactions on Portuguese merchants following the conquest of Malacca,[83] sinophobia became widespread in Portugal, and widely practiced until the First Opium War, which the Qing dynasty was forced to cede Macao to Portugal.[84][note 2]

Russia

[edit]Spain

[edit]Spain first issued anti-Chinese legislation when Limahong, a Chinese pirate, attacked Spanish settlements in the Philippines. One of his famous actions was a failed invasion of Manila in 1574, which he launched with the support of Chinese and Moro pirates.[85] The Spanish conquistadors massacred the Chinese or expelled them from Manila several times, notably the autumn 1603 massacre of Chinese in Manila, and the reasons for this uprising remain unclear. Its motives range from the desire of the Chinese to dominate Manila, to their desire to abort the Spaniards' moves which seemed to lead to their elimination. The Spaniards quelled the rebellion and massacred around 20,000 Chinese. The Chinese responded by fleeing to the Sulu Sultanate and supporting the Moro Muslims in their war against the Spanish. The Chinese supplied the Moros with weapons and joined them in directly fighting against the Spanish during the Spanish–Moro conflict. Spain also upheld a plan to conquer China, but it never materialized.[86]

United Kingdom

[edit]15% of ethnic Chinese reported racial harassment in 2016, which was the highest percentage out of all ethnic minorities in the UK.[87] The Chinese community has been victims of racially-aggravated attacks and murders, verbal accounts of racism, and vandalism. There is also a lack of reporting on anti-Chinese discrimination in the UK, notably violence against Chinese Britons.[88]

The ethnic slur "chink" has been used against the Chinese community; Dave Whelan, the former owner of Wigan Athletic, was fined £50,000 and suspended for six weeks by The Football Association after using the term in an interview; Kerry Smith resigned as an election candidate after it was reported he used similar language.[88]

Professor Gary Craig from Durham University carried out research about the Chinese population in the UK, and concluded that hate crimes against the Chinese community are getting worse, adding that British Chinese people experience "perhaps even higher levels of racial violence or harassment than those experienced by any other minority group but that the true extent to their victimization is often overlooked because victims were unwilling to report it."[88] Official police victim statistics put Chinese people in a group that includes other ethnicities, making it difficult to understand the extent of the crimes against the Chinese community.[88]

Americas

[edit]Canada

[edit]In the 1850s, sizable numbers of Chinese immigrants came to British Columbia during the gold rush; the region was known to them as Gold Mountain. Starting in 1858, Chinese "coolies" were brought to Canada to work in the mines and on the Canadian Pacific Railway. However, they were denied by law the rights of citizenship, including the right to vote, and in the 1880s, "head taxes" were implemented to curtail immigration from China. In 1907, a riot in Vancouver targeted Chinese and Japanese-owned businesses. In 1923, the federal government banned Chinese immigration outright,[22]: 31 passing the Chinese Immigration Act, commonly known as the Exclusion Act, prohibiting further Chinese immigration except under "special circumstances". The Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947, the same year in which Chinese Canadians were given the right to vote. Restrictions would continue to exist on immigration from Asia until 1967 when all racial restrictions on immigration to Canada were repealed, and Canada adopted the current points-based immigration system. On June 22, 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered an apology and compensation only for the head tax once paid by Chinese immigrants.[89] Survivors or their spouses were paid approximately CA$20,000 in compensation.[90]

Mexico

[edit]Anti-Chinese sentiment was first recorded in Mexico in 1880s. Similar to most Western countries at the time, Chinese immigration and its large business involvement have always been a fear for native Mexicans. Violence against Chinese occurred such as in Sonora, Baja California and Coahuila, the most notable was the Torreón massacre.[91]

Peru

[edit]Peru was a popular destination for Chinese slaves in the 19th century, as part of the wider blackbirding phenomenon, due to the need in Peru for a military and laborer workforce. However, relations between Chinese workers and Peruvian owners have been tense, due to the mistreatment of Chinese laborers and anti-Chinese discrimination in Peru.[23]

Due to the Chinese support for Chile throughout the War of the Pacific, relations between Peruvians and Chinese became increasingly tenser in the aftermath. After the war, armed indigenous peasants sacked and occupied haciendas of landed elite criollo "collaborationists" in the central Sierra – the majority of them were of ethnic Chinese, while indigenous and mestizo Peruvians murdered Chinese shopkeepers in Lima; in response to Chinese coolies revolted and even joined the Chilean Army.[92][93] Even in the 20th century, the memory of Chinese support for Chile was so deep that Manuel A. Odría, once dictator of Peru, issued a ban against Chinese immigration as a punishment for their betrayal.[94]

United States

[edit]

Starting with the California Gold Rush in the 19th century, the United States—particularly the West Coast states—imported large numbers of Chinese migrant laborers. Employers believed that the Chinese were "reliable" workers who would continue working, without complaint, even under harsh conditions.[95] The migrant workers encountered considerable prejudice in the United States, especially among the people who occupied the lower layers of white society, because Chinese "coolies" were used as scapegoats for depressed wage levels by politicians and labor leaders.[96] Cases of physical assaults on the Chinese include the Chinese massacre of 1871 in Los Angeles. The 1909 murder of Elsie Sigel in New York, for which a Chinese person was suspected, was blamed on the Chinese in general and it immediately led to physical violence against them. "The murder of Elsie Sigel immediately grabbed the front pages of newspapers, which portrayed Chinese men as dangerous to "innocent" and "virtuous" young white women. This murder led to a surge in the harassment of Chinese in communities across the United States."[97]

The emerging American trade unions, under such leaders as Samuel Gompers, also took an outspoken anti-Chinese position,[98] regarding Chinese laborers as competitors to white laborers. Only with the emergence of the international trade union, IWW, did trade unionists start to accept Chinese workers as part of the American working class.[99]

In the 1870s and 1880s, various legal discriminatory measures were taken against the Chinese. These laws, in particular, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, were aimed at restricting further immigration from China.[21] although the laws were later repealed by the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943. In particular, even in his lone dissent against Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), then-Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote of the Chinese as: "a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race."[100]

In April 2008, CNN's Jack Cafferty remarked: "We continue to import their junk with the lead paint on them and the poisoned pet food [...] So I think our relationship with China has certainly changed. I think they're basically the same bunch of goons and thugs they've been for the last 50 years." At least 1,500 Chinese Americans protested outside CNN's Hollywood offices in response while a similar protest took place at CNN headquarters in Atlanta.[101][102]

Anti-Han sentiment

[edit]Anti-Han sentiment refers to fear or dislike ethnic Han people. Anti-Han sentiment includes hostility towards Han Taiwanese as well as mainland Han Chinese.[103] Since the proportion of Han people in China's ethnic composition is absolute, the anti-Han sentiment is closely related to the anti-Chinese sentiment.

Historical acts of Sinophobic violence

[edit]List of non-Chinese "sinophobia-led" acts of violence against ethnic Chinese:

Australia

[edit]Canada

[edit]Mexico

[edit]Mongolia

[edit]- Mongol conquest of China

- Deportation of Chinese people to China in the 1960's

- Attacks against Chinese by the Tsagaan Khas

Indonesia

[edit]- 1740 Batavia massacre

- 1918 Kudus riot

- Mergosono massacre

- Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66

- 1967 Mangkuk Merah Tragedy

- 1980 Jawa Tengah Racial Riot

- Situbondo Riot

- Banjarmasin riot of May 1997

- May 1998 riots of Indonesia

- November 2016 Jakarta protests

Malaysia

[edit]Japan

[edit]

By Koreans

[edit]- Wanpaoshan Incident, on July 1, 1931

United States

[edit]- Chinese massacre of 1871

- Rock Springs massacre

- Issaquah riot of 1885

- Tacoma riot of 1885

- Seattle riot of 1886

- Hells Canyon Massacre

- Anti-Chinese violence in California

- Denver Riot of 1880

- Killing of Vincent Chin

Vietnam

[edit]Derogatory terms

[edit]There are a variety of derogatory terms for Chinese people. Many of these terms are racist.

In English

[edit]- Chinaman – the term Chinaman is noted as offensive by modern dictionaries, dictionaries of slurs and euphemisms, and guidelines for racial harassment.

- Ching chong – Used to mock people of Chinese descent and the Chinese language, or other East and Southeast Asian-looking people in general.

- Ching chang chong – same usage as 'ching chong'.

- Chink – a racial slur referring to a person of Chinese ethnicity, but could be directed towards anyone of East and Southeast Asian descent in general.

- Chinky – the name "Chinky" is the adjectival form of Chink and, like Chink, is an ethnic slur for Chinese occasionally directed towards other East and Southeast Asian people.

- Chonky – refers to a person of Chinese heritage with white attributes whether being a personality aspect or physical aspect.[105][106]

- Coolie – means laborer in reference to Chinese manual workers in the 19th and early 20th century.

- Slope – used to mock people of Chinese descent and the sloping shape of their skull, or other East Asians. Used commonly during the Vietnam War.

- Panface – used to mock the flat facial features of the Chinese and other people of East and Southeast Asian descent.

- Lingling – used to call someone of Chinese descent in the West.

In Filipino

[edit]- Intsik (Cebuan: Insik) is used to refer to refer people of Chinese ancestry including Chinese Filipinos. (The standard term is Tsino, derived from the Spanish chino, with the colloquial Tsinoy referring specifically to Chinese Filipinos.) The originally neutral term recently gained negative connotation with the increasing preference of Chinese Filipinos not to be referred to as Intsik. The term originally came from in chiek, a Hokkien term referring to one's uncle. The term has variations, which may be more offensive in tone such as Intsik baho and may used in a derogatory phrase, Intsik baho tulo-laway ("Smelly old Chinaman with drooling saliva").[107][108]

- Tsekwa (sometimes spelled chekwa) – is a slang term used by the Filipinos to refer to Chinese people.[109]

In French

[edit]- Chinetoque (m/f) – derogatory term referring to Asian people, especially of those from China and Vietnam.

In Indonesian

[edit]- Chitato – (China Tanpa Toko) – literally "Chinese people don't have shops" referring to ridicule for Indonesian Chinese descent who do not own shops.

- Aseng – A play on the word "asing" which means "foreigner" is used by local natives in Indonesia for Chinese descent.

- Panlok (Panda lokal/local panda) – derogatory term referring to Chinese female or female who look like Chinese, particularly prostitutes.[110]

In Japanese

[edit]- Dojin (土人, dojin) – literally "earth people", referring either neutrally to local folk or derogatorily to indigenous peoples and savages, used towards the end of the 19th century and early 20th century by Japanese colonists, to imply the backwardsness of Chinese people.[111]

- Shina (支那 or シナ, shina) – Japanese reading of the Chinese character compound "支那" (Zhina in Mandarin Chinese), originally a Chinese transcription of an Indic name for China that entered East Asia with the spread of Buddhism. This toponym quickly became a racial marker with the rise of Japanese imperialism,[112] and it is still considered derogatory, as is 'shina-jin'.[113][114] The slur is also extended toward left-wing activists by right-wing people.[115]

- Chankoro (チャンコロ or ちゃんころ, chankoro) – derogatory term originating from a corruption of the Taiwanese Hokkien pronunciation of 清國奴 Chheng-kok-lô͘, used to refer to any "Chinaman", with a meaning of "Qing dynasty's slave".

In Korean

[edit]- Jjangkkae [ko] (Korean: 짱깨) – the Korean pronunciation of 掌櫃 (zhǎngguì), literally "shopkeeper", originally referring to owners of Chinese restaurants and stores;[116] derogatory term referring to Chinese people.

- Jjangkkolla [ko] (Korean: 짱꼴라) – this term has originated from Japanese term chankoro (淸國奴, lit. "slave of Qing Manchurian"). Later, it became a derogatory term that indicates people in China.[117]

- Orangkae (Korean: 오랑캐) – literally "Barbarian", derogatory term used against Chinese, Mongolian and Manchus.

- Doenom (Korean: 되놈) – Originally a demeaning word for Jurchen, meaning something similar to 'barbarian'. The Jurchens invaded Joseon in 1636 and caused long-term hatred. A Jurchen group later made the Qing dynasty, causing some Koreans to generalize the word to China as a whole.[118]

- Ttaenom (Korean: 때놈) – literally "dirt bastard", referring to the perceived "dirtiness" of Chinese people, who some believe do not wash themselves. It was originally Dwoenom but changed over time to Ddaenom.

In Mongolian

[edit]- Hujaa (Mongolian: хужаа) – derogatory term referring to Chinese people.

- Jungaa – a derogatory term for Chinese people referring to the Chinese language.

In Portuguese

[edit]- Pastel de flango (Chicken pastry) - it is a derogatory term ridiculing Chinese pronunciation of Portuguese language (changing R by L). This derogatory term is sometimes used in Brazil to refer to Chinese people.[119]

In Russian

[edit]- Kitayoza (Russian: китаёза kitayóza) (m/f) – derogatory term referring to Chinese people.

- Uzkoglazy (Russian: узкоглазый uzkoglázy) (m) – generic derogatory term referring to Chinese people (lit. "narrow-eyed").

In Spanish

[edit]- Chino cochino – (coe-chee-noe, N.A. "cochini", SPAN "cochino", literally meaning "pig") is an outdated derogatory term meaning dirty Chinese. Cochina is the feminine form of the word.

In Italian

[edit]- Muso giallo – "yellow muzzle/yellow face", this term was used in an early 20th century play regarding Italian miners. Although it was not directed toward a Chinese person, but rather from one Italian to another, its existence nevertheless attested to the perceived 'otherness' of Chinese laborers within Italy.[120] The slur is used as an equivalent of "gook" or "zipperhead" in Italian dubs of English films.[121]

In Thai

[edit]- Chek/Jek (Thai: เจ๊ก) – derogatory term referring to Chinese people.

In Vietnamese

[edit]- Tàu – literally "boat". It is used to refer to Chinese people in general, and can be construed as derogatory but very rarely does. This usage is derived from the fact that many Chinese refugees came to Vietnam in boats during the Qing dynasty.[122]

- Khựa – (meaning dirty) derogatory term for Chinese people and combination of two words above is called Tàu Khựa, which is a common word.[122]

- Chệc – (ethnic slur, derogatory) Chink[123][124]

- Chệch[note 3] – (ethnic slur, derogatory) Chink, seldom used in actual spoken Vietnamese, but occurs in some translations as an equivalent of English Chink.

Sinophobia during the COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]

The COVID-19 pandemic, in which the virus was first detected in Wuhan, has caused prejudice and racism against people of Chinese ancestry; some people stated that Chinese people deserve to contract it.[126][127] This led to multiple acts of severe violence against people of Chinese ancestry, and those supposed, wrongly, to have been of Chinese ancestry as well.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, victims of violence and verbal abuse range from toddlers to elderly,[17] school children and their parents,[14] and include not just mainland Chinese, but has affected also Taiwanese, Hong Kongers, members of the Chinese diaspora and other Asians who are mistaken for or associated with them.[16][14]

Several citizens across the globe also demanded a ban on Chinese people from their countries.[128][129] Racist abuse and assaults among Asian groups in the UK and US have also increased.[130][131] Former U.S. President Donald Trump also repeatedly called the coronavirus 'Chinese virus',[132][133] however, he denied the term had a racist connotation.[134]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In Sinosphere, "anti-Chinese government" (反中[國], lit. "anti-Chinese [state]), "anti-Communist" (反共 / 反中共) or "anti-People's Republic of China" (反中華人民共和國), which means political opposition to the Chinese government or state, is distinct from "anti-Chinese racism" (反華 / 嫌中), which is a racist hatred of the Chinese people.[10][11]

- ^ Macao was a trading outpost of Portugal since the 1600s in an agreement between China and Portugal, as a non-sovereign holding of the Portuguese empire. The "cession" referred to here is that the sovereignty of Macao was ceded for the first time by China to Portugal after the defeat in the Opium Wars.

- ^ Alternative form of Chệc.

References

[edit]- ^ "Sinophobia is "Fear of or contempt for China, its people, or its culture" states The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Online Edition. Retrieved July 12, 2012". Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ Macmillan dictionary. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ The Free Dictionary By Farlex. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Collons Dictionary. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ hksspr (January 31, 2024). "Chinese-Indonesians Face Long Road to National Integration, Except During Elections". HKS Student Policy Review. Archived from the original on July 11, 2024. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ "Minority Rights - Chinese in the Philippines". Minority Rights. October 16, 2023. Archived from the original on July 6, 2024. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "Analysis – Indonesia: Why ethnic Chinese are afraid". Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Aaron Langmaid. Chinese Aussie rules players suffer abuse, racism Archived April 5, 2023, at the Wayback Machine Herald Sun February 21, 2013

- ^ a b Kazin, Michael; Edwards, Rebecca; Rothman, Adam (2010). "Immigration Policy". The Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History. Princeton University Press.

Compared to its European counterparts, Chinese immigration of the late nineteenth century was minuscule (4 percent of all immigration at its zenith), but it inspired one of the most brutal and successful nativist movements in U.S. history. Official and popular racism made Chinese newcomers especially vulnerable; their lack of numbers, political power, or legal protections gave them none of the weapons that enabled Irish Catholics to counterattack nativists.

- ^ Chih-yu Shih; Prapin Manomaivibool; Reena Marwah (August 13, 2018). China Studies In South And Southeast Asia: Between Pro-china And Objectivism. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 36.

- ^ 紀紅兵; 內幕出版社 (August 25, 2016). 《十九大不准奪權》: 反貪─清除野心家 (in Chinese). 內幕出版社. ISBN 978-1-68182-072-9. Archived from the original on August 26, 2024. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

... 第三點,作為獨立學者,與您分享下本人"反中不反華"的觀點。

- ^ a b William F. Wu, The Yellow Peril: Chinese Americans in American Fiction, 1850–1940, Archon Press, 1982.

- ^ "Conference Indorses Chinese Exclusion; Editor Poon Chu Says China Will Demand Entrance Some Day – A Please for the Japanese – Committee on Resolutions Commends Roosevelt's Position as Stated in His Message". The New York Times. December 9, 1905. p. 5. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c Cheah, Charissa S. L.; Ren, Huiguang; Zong, Xiaoli; Wang, Cixin. "COVID-19 Racism and Chinese American Families' Mental Health: A Comparison between 2020 and 2021". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 20 (8). ISSN 1660-4601.

- ^ Tahmasbi, Fatemeh; Schild, Leonard; Ling, Chen; Blackburn, Jeremy; Stringhini, Gianluca; Zhang, Yang; Zannettou, Savvas (June 3, 2021). ""Go eat a bat, Chang!": On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19". Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021. WWW '21. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1122–1133. doi:10.1145/3442381.3450024. ISBN 978-1-4503-8312-7.

- ^ a b Viladrich, Anahí (2021). "Sinophobic Stigma Going Viral: Addressing the Social Impact of COVID-19 in a Globalized World". American Journal of Public Health. 111 (5): 876–880. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2021.306201. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 8034019. PMID 33734846.

- ^ a b Gao, Zhipeng (2022). "Sinophobia during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Identity, Belonging, and International Politics". Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science. 56 (2): 472–490. doi:10.1007/s12124-021-09659-z. ISSN 1932-4502. PMC 8487805. PMID 34604946.

- ^ Sengul, Kurt (May 3, 2024). "The (Re)surgence of Sinophobia in the Australian Far-Right: Online Racism, Social Media, and the Weaponization of COVID-19". Journal of Intercultural Studies. 45 (3): 414–432. doi:10.1080/07256868.2024.2345624. ISSN 0725-6868.

- ^ Billé, Franck (October 31, 2014). Sinophobia: Anxiety, Violence, and the Making of Mongolian Identity. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824847838 – via www.degruyter.com.

- ^ Lovell, Julia (November 10, 2015). The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of Modern China. Overlook Press. ISBN 9781468313239.

- ^ a b "An Evidentiary Timeline on the History of Sacramento's Chinatown: 1882 – American Sinophobia, The Chinese Exclusion Act and "The Driving Out"". Friends of the Yee Fow Museum, Sacramento, California. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2008.

- ^ a b Crean, Jeffrey (2024). The Fear of Chinese Power: an International History. New Approaches to International History series. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-23394-2.

- ^ a b Justina Hwang. Chinese in Peru in the 19th century Archived November 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine - Modern Latin American, Brown University Library.

- ^ a b Unspeakable Affections Archived November 16, 2019, at the Wayback Machine - Paris Review. May 5, 2017.

- ^ Daniel Renshaw, "Prejudice and paranoia: a comparative study of antisemitism and Sinophobia in turn-of-the-century Britain." Patterns of Prejudice 50.1 (2016): 38-60. online Archived February 29, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tai, Crystal (January 5, 2018). "The strange, contradictory privilege of living in South Korea as a Chinese-Canadian woman". Quartz. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Anti Chinese-Korean Sentiment on Rise in Wake of Fresh Attack". KoreaBANG. April 25, 2012. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "Hate Speech against Immigrants in Korea: A Text Mining Analysis of Comments on News about Foreign Migrant Workers and Korean Chinese Residents* (page 281)" (PDF). Seoul National University. Ritsumeikan University. January 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2020.

- ^ "Ethnic Korean-Chinese fight 'criminal' stigma in Korea". AsiaOne. October 4, 2017. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "'반중 넘어 혐중'‥ 중국인 혐오, 도 넘은 수준까지?". The Financial News (in Korean). June 13, 2019. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Joint Civil Society Report on Racial Discrimination in Japan (page 33)" (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. August 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Issues related to the increase in tourists visiting Japan from abroad (sections titled 'How foreign tourists are portrayed' and 'Acts of hate?')". www.japanpolicyforum.jp. November 2017. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Tania Branigan (August 2, 2010). "Mongolian neo-Nazis: Anti-Chinese sentiment fuels rise of ultra-nationalism". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Billé (2015). Sinophobia: Anxiety, Violence, and the Making of Mongolian Identity.

- ^ Avery, Martha (2003). The Tea Road: China and Russia Meet Across the Steppe. China Intercontinental Press. p. 91.[circular reference]

- ^ Horowitz, Donald L. (2003). The Deadly Ethnic Riot. University of California Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0520236424.

- ^ "Penang's forgotten protest: The 1967 Hartal". Penang Monthly. August 25, 2014. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Horowitz, Donald L. (2003). The Deadly Ethnic Riot. University of California Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0520236424.

- ^ Hwang, p. 72.

- ^ von Vorys 1975, p. 364.

- ^ "RACE WAR IN MALAYSIA". TIME. May 18, 2007. Archived from the original on May 18, 2007.

- ^ von Vorys 1975, p. 368.

- ^ Slimming 1969, pp. 47–48.

- ^ "A Revision of Malaysia's Racial Compact". Harvard Political Review. August 18, 2021. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021.

- ^ Menon, Praveen (March 9, 2018). "Attack on Chinese billionaire exposes growing racial divide in Malaysia". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Amy Chew (September 10, 2019). "In Malaysia, fake news of Chinese nationals getting citizenship stokes racial tensions". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Tantingco, Robby (March 15, 2010). "Tantingco: What your surname reveals about your past". Sunstar. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ James Francis Warren (2007). The Sulu zone, 1768–1898: the dynamics of external trade, slavery, and ethnicity in the transformation of a Southeast Asian maritime state (2, illustrated ed.). NUS Press. pp. 129, 130, 131. ISBN 978-9971-69-386-2. Archived from the original on August 26, 2024. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Chu, Richard T. (May 1, 2011). "Strong(er) Women and Effete Men: Negotiating Chineseness in Philippine Cinema at a Time of Transnationalism". Positions: Asia Critique. 19 (2). Duke University Press: 365–391. doi:10.1215/10679847-1331760. ISSN 1067-9847. S2CID 146678795. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ History: October 9, 1740: Chinezenmoord, The Batavia Massacre. Posted on History Headline. Posted by Major Dan on October 9, 2016.

- ^ 海外汉人被屠杀的血泪史大全. woku.com (in Simplified Chinese). [permanent dead link]

- ^ 十七﹒八世紀海外華人慘案初探 (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Taoyuan Department of Education. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ "ǻܵļɱ". Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ 南洋华人被大规模屠杀不完全记录 (in Chinese (China)). The Third Media. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- ^ Indonesian academics fight burning of books on 1965 coup Archived January 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, smh.com.au

- ^ Vickers (2005), p. 158

- ^ "Inside Indonesia – Digest 86 – Towards a mapping of 'at risk' groups in Indonesia". Archived from the original on September 20, 2000. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "[Indonesia-L] Digest – The May Riot". Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Nicholas Farrelly, Stephanie Olinga-Shannon. "Establishing Contemporary Chinese Life in Myanmar (pages 24, 25)" (PDF). ISEAS Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Han, Enze (2024). The Ripple Effect: China's Complex Presence in Southeast Asia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-769659-0.

- ^ Luang Phibunsongkhram Archived August 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. Posted in Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "Nation-building and the Pursuit of Nationalism under Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram". 2bangkok.com. July 15, 2004. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "overseas chinese in vietnam". Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Tretiak, Daniel (1979). "China's Vietnam War and Its Consequences". The China Quarterly. 80 (80). Cambridge University Press: 740–767. doi:10.1017/S0305741000046038. JSTOR 653041. S2CID 154494165. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wang, Frances Yaping (2024). The Art of State Persuasion: China's Strategic Use of Media in Interstate Disputes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197757512.

- ^ Griffin, Kevin. Vietnamese Archived February 28, 2003, at the Wayback Machine. Discover Vancouver.

- ^ a b c Mazumdar, Jaideep (November 20, 2010). "The 1962 jailing of Chinese Indians". OPEN. Archived from the original on December 18, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- ^ Schiavenza, Matt (August 9, 2013). "India's Forgotten Chinese Internment Camp". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- ^ Young, Jason. "Review of East by South: China in the Australasian Imagination". Victoria University of Wellington. Archived from the original (.doc) on April 14, 2008. Retrieved March 24, 2008.

- ^ a b Markey, Raymond (January 1, 1996). "Race and organized labor in Australia, 1850–1901". The Historian. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2006.

- ^ a b Griffiths, Phil (July 4, 2002). "Towards White Australia: The shadow of Mill and the spectre of slavery in the 1880s debates on Chinese immigration" (RTF). 11th Biennial National Conference of the Australian Historical Association. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2006.

- ^ Giese, Diana (1995). Beyond Chinatown (PDF). National Library of Australia. pp. 35–37. ISBN 0642106339. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "PNG riots hit Chinese businesses". BBC. May 18, 2009. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "Overseas and under siege". The Economist. 2009. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on July 27, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ "No More Chinese!" Archived June 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Tongatapu.net

- ^ a b "The Pacific Proxy: China vs Taiwan" Archived November 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Graeme Dobell, ABC Radio Australia, February 7, 2007

- ^ "Chinese stores looted in Tonga riots" Archived May 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, People's Daily, November 17, 2006

- ^ a b c Ponniah, Kevin (October 26, 2016). "A killing in Paris: Why French Chinese are in uproar". BBC. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ "A killing in Paris: Why French Chinese are in uproar". BBC News. October 25, 2016. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ How did the Boxer Rebellion unite Imperial Powers and create Chinese Nationalism? Archived March 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Posted on Daily History.

- ^ Carbone, Iside (January 12, 2015). China in the Frame: Materialising Ideas of China in Italian Museums. Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 9781443873062.

- ^ Ricardo Padron (2014).Sinophobia vs. Sinofilia in the 16th Century Iberian World Archived July 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Instituto Cultural do Governo da R.A.E de Macau.

- ^ Cameron, Nigel (1976). Barbarians and mandarins: thirteen centuries of Western travelers in China. Vol. 681 of A phoenix book (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-226-09229-4. Archived from the original on August 26, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

envoy, had most effectively poured out his tale of woe, of deprivation at the hands of the Portuguese in Malacca; and he had backed up the tale with others concerning the reprehensible Portuguese methods in the Moluccas, making the case (quite truthfully) that European trading visits were no more than the prelude to annexation of territory. With the tiny sea power at this time available to the Chinese

- ^ Duarte Drumond Braga (2017). de portugal a macau: Filosofia E Literatura No Diálogo Das Culturas Archived May 30, 2024, at the Wayback Machine. Universidade do Porto, Faculdade de Letras.

- ^ The story of Li-ma-hong and his failed attempt to conquer Manila in 1574 Archived July 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Posted on Wednesday October 24, 2012.

- ^ Samuel Hawley. The Spanish Plan to Conquer China Archived July 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Doward, Jamie; Hyman, Mika (November 19, 2017). "Chinese report highest levels of racial harassment in UK". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Thomas, Emily (January 6, 2015). "British Chinese people say racism against them is 'ignored'". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Canada (2006). "Address by the Prime Minister on the Chinese Head Tax Redress". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- ^ PM apologizes in House of Commons for head tax Archived February 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ An anti-Chinese mob in Mexico Archived May 2, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. New York Times.

- ^ Taylor, Lewis. Indigenous Peasant Rebellions in Peru during the 1880s

- ^ Bonilla, Heraclio. 1978. The National and Colonial Problem in Peru. Past and Present

- ^ López-Calvo, Ignacio; Chang-Rodríguez, Eugenio (2014). Dragons in the Land of the Condor: Writing Tusán in Peru. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816531110. Retrieved April 22, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Norton, Henry K. (1924). The Story of California From the Earliest Days to the Present. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co. pp. 283–296. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ See, e.g., "Our Misery and Despair": Kearney Blasts Chinese Immigration Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Posted on History Matters: The U.S. Survey course on the web. Posted by Dennis Kearney, President, and H.L Knight, Secretary.

- ^ Ling, Huping (2004). Chinese St. Louis: From Enclave to Cultural Community. Temple University Press. p. 68.

The murder of Elsie Sigel immediately grabbed the front pages of newspapers, which portrayed Chinese men as dangerous to "innocent" and "virtuous" young white women. This murder led to a surge in the harassment of Chinese in communities across the United States.

- ^ Gompers, Samuel; Gustadt, Herman (1902). Meat vs. Rice: American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism: Which Shall Survive?. American Federation of Labor.

- ^ Lai, Him Mark; Hsu, Madeline Y. (2010). Chinese American Transnational Politics. University of Illinois Press. pp. 53–54.

- ^ Chin, Gabriel J. "Harlan, Chinese and Chinese Americans". University of Dayton Law School. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ^ Pierson, David (April 20, 2008). "Protesters gather at CNN". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021.

- ^ Chris Berdik (April 25, 2008). "Is the World Against China? | BU Today". Boston University. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Anti-Han Sentiment as a Risk for the New Southbound Policy". Global Taiwan Institute. July 19, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ Amy Chua (January 6, 2004). World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4000-7637-6.

- ^ Fontes, Lisa Aronson (May 23, 2008). ?. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-59385-710-3.

- ^ Robert Lee, A (January 28, 2008). ?. Rodopi. ISBN 9789042023512. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ "Pinoy or Tsinoy, What is the Problem?". September 13, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Intsik". Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Pinoy Slang - Tsekwa". Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ "Kamus Slang Mobile". kamusslang.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017.

- ^ Howell, David L. (February 7, 2005). Geographies of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan. University of California Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-520-93087-2.

- ^ LIU, Lydia He (June 30, 2009). The Clash of Empires: the invention of China in modern world making. Harvard University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-674-04029-8.

- ^ Song, Weijie (November 17, 2017). Mapping Modern Beijing: Space, Emotion, Literary Topography. Oxford University Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-19-069284-1.

- ^ Lim, David C. L. (June 30, 2008). Overcoming Passion for Race in Malaysia Cultural Studies. BRILL. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-474-3370-5.

- ^ "Police officer dispatched from Osaka insults protesters in Okinawa". The Japan Times Online. October 19, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ 중국, 질문 좀 할게 (in Korean). 좋은땅. April 22, 2016. p. 114. ISBN 9791159820205. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ (in Korean) Jjangkkolla – Naver encyclopedia

- ^ "떼놈. 때놈. 뙤놈?". December 13, 2014.

- ^ "'Pastel de flango'? Racismo anti-amarelos não é mimimi". Capricho (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Randall, Annie J.; Davis, Rosalind Gray (2005). Puccini and The Girl: History and Reception of The Girl of the Golden West. University of Chicago Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-226-70389-3.

- ^ Giampieri, Patrizia (June 23, 2017). "Racial slurs in Italian film dubbing". Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts. 3 (2): 262–263. doi:10.1075/ttmc.3.2.06gia.

- ^ a b Nguyễn, Ngọc Chính (May 27, 2019). "Ngôn ngữ Sài Gòn xưa: Những vay mượn từ người Tàu". Khoa Việt Nam Học.

Người ta còn dùng các từ như Khựa, Xẩm, Chú Ba… để chỉ người Tàu, cũng với hàm ý miệt thị, coi thường.

- ^ Pham, Ngoc Thuy Vi. "The Educational Development of the Chinese Community in Southern Vietnam" (PDF). National Cheng Kung University. p. 6.

Also, according to the "Dictionnaire Annamite–français", "Chec" (Chệc) was the nickname that the Vietnamese people at that time used for Huaqiao. "Chệc" was also how the Annamites called the ethnic Chinese in an unfriendly way. (Chệc: Que les Annamites donnent aux Chinois surnom en mauvaise partie) (J. F. M. Genibrel 1898: 79).

- ^ Nguyễn, Ngọc Chính (May 27, 2019). "Ngôn ngữ Sài Gòn xưa: Những vay mượn từ người Tàu". Khoa Việt Nam Học.

"…Còn kêu là Chệc là tại tiếng Triều Châu kêu tâng Chệc nghĩa là chú. Người bên Tàu hay giữ phép, cũng như An-nam ta, thấy người ta tuổi đáng cậu, cô, chú, bác thì kêu tâng là chú là cậu vân vân. Người An-nam ta nghe vậy vịn theo mà kêu các ảnh là Chệc…"

- ^ O'Hara, Mary Emily. "Mock Subway Posters Urge New Yorkers to Curb Anti-Asian Hate". www.adweek.com. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "'You deserve the coronavirus': Chinese people in UK abused over outbreak". Sky News. February 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Nicola; Torre, Giovanni (February 1, 2020). "Anti-Chinese racism spikes as virus spreads globally". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

'Some Muslims stated that the disease was "divine retribution" for China's oppression of the Uighur minority. The problem lay in confusing the Chinese population with the actions of an authoritarian government which is known for its lack of transparency,' he stated.

- ^ Solhi, Farah (January 26, 2020). "Some Malaysians calling for ban on Chinese tourists". New Straits Times.

- ^ Cha, Hyonhee Shin (January 28, 2020). "South Koreans call in petition for Chinese to be barred over virus". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Tavernise, Sabrina; Oppel, Richard A. Jr. (March 23, 2020). "Spit On, Yelled At, Attacked: Chinese-Americans Fear for Their Safety". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Hunt for racist coronavirus attackers: Police release CCTV after assault". ITV News. March 4, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Rogers, Katie; Jakes, Lara; Swanson, Ana (March 18, 2020). "Trump Defends Using 'Chinese Virus' Label, Ignoring Growing Criticism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Trump: Asian-Americans not responsible for virus, need protection". Reuters. March 24, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "'Not racist at all': Donald Trump defends calling coronavirus the 'Chinese virus'". The Guardian -- YouTube. March 18, 2020. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Aarim-Heriot, Najia (2003). Chinese Immigrants, African Americans, and Racial Anxiety in the United States, 1848–82. University of Illinois Press.

- Ang, Sylvia, and Val Colic-Peisker. "Sinophobia in the Asian century: race, nation and Othering in Australia and Singapore." Ethnic and racial studies 45.4 (2022): 718–737. online

- Billé, Franck. Sinophobia : anxiety, violence, and the making of Mongolian identity (2015) online

- Chua, Amy. World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability (Random House Digital, 2004) online

- Ferrall, Charles; Millar, Paul; Smith, Keren. (eds.) (2005). East by South: China in the Australasian imagination. Victoria University Press.

- Hong, Jane H. Opening the Gates to Asia: A Transpacific History of How America Repealed Asian Exclusion (University of North Carolina Press, 2019) online review

- Jain, Shree, and Sukalpa Chakrabarti. "The Dualistic Trends of Sinophobia and Sinophilia: Impact on Foreign Policy Towards China." China Report 59.1 (2023): 95–118. doi.org/10.1177/00094455231155212

- Lew-Williams, Beth. The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America (Harvard UP, 2018)

- Lovell, Julia. The Great Wall: China against the world, 1000 bc–ad 2000 (Grove/Atlantic, 2007). online

- Lovell, Julia. Maoism: A Global History (2019), a comprehensive scholarly history excerpt

- Lovell, Julia. "The Uses of Foreigners in Mao-Era China: 'Techniques of Hospitality' and International Image-Building in the People's Republic, 1949–1976." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 25 (2015): 135–158. online

- McClain, Charles J. (1996). In Search of Equality: The Chinese Struggle Against Discrimination in Nineteenth-Century America. University of California Press.

- Mungello, David E. (2009). The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Ngai, Mae. The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics (2021), Mid 19c in California, Australia, and South Africa

- Ratuva, Steven. "The Politics of Imagery: Understanding the Historical Genesis of Sinophobia in Pacific Geopolitics." East Asia 39.1 (2022): 13–28. online

- Renshaw, Daniel. "Prejudice and paranoia: a comparative study of antisemitism and Sinophobia in turn-of-the-century Britain." Patterns of Prejudice 50.1 (2016): 38–60. around year 1900. online

- Schumann, Sandy, and Ysanne Moore. "The COVID-19 outbreak as a trigger event for sinophobic hate crimes in the United Kingdom." British Journal of Criminology 63.2 (2023): 367–383. online

- Slimming, John (1969). The Death of a Democracy. John Murray Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7195-2045-7. Book written by an Observer/UK journalist, who was in Kuala Lumpur at the time.

- Tsolidis, Georgina. "Historical Narratives of Sinophobia–Are these echoed in contemporary Australian debates about Chineseness?." Journal of Citizenship and Globalisation Studies 2.1 (2018): 39–48. online

- von Vorys, Karl (1975). Democracy Without Consensus: Communalism and Political Stability in Malaysia. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07571-6. Paperback reprint (2015) ISBN 9780691617640.

- Ward, W. Peter (2002). White Canada Forever: Popular Attitudes and Public Policy Toward Orientals in British Columbia. McGill-Queen's Press. 3rd edition.

- Witchard, Anne. England's Yellow Peril: Sinophobia and the Great War (2014) excerpt

External links

[edit] Media related to Anti-Chinese sentiment at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Anti-Chinese sentiment at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of Sinophobia at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Sinophobia at Wiktionary